Introduction

Stress is often viewed as a challenge adults face, but growing evidence shows that stress experienced in childhood can have profound and long-lasting effects on brain development. In 2025, neuroscientists, psychologists, and pediatricians are intensifying their focus on how early-life stress influences the structure, function, and chemistry of the developing brain. This growing body of research underscores the importance of early intervention, supportive environments, and public health strategies to mitigate the impact of childhood stress.

The Science of Stress and the Developing Brain

During childhood, the brain undergoes rapid development, forming essential neural circuits and connections that support learning, behavior, and emotional regulation. However, exposure to chronic or intense stress during this sensitive period can disrupt these processes.

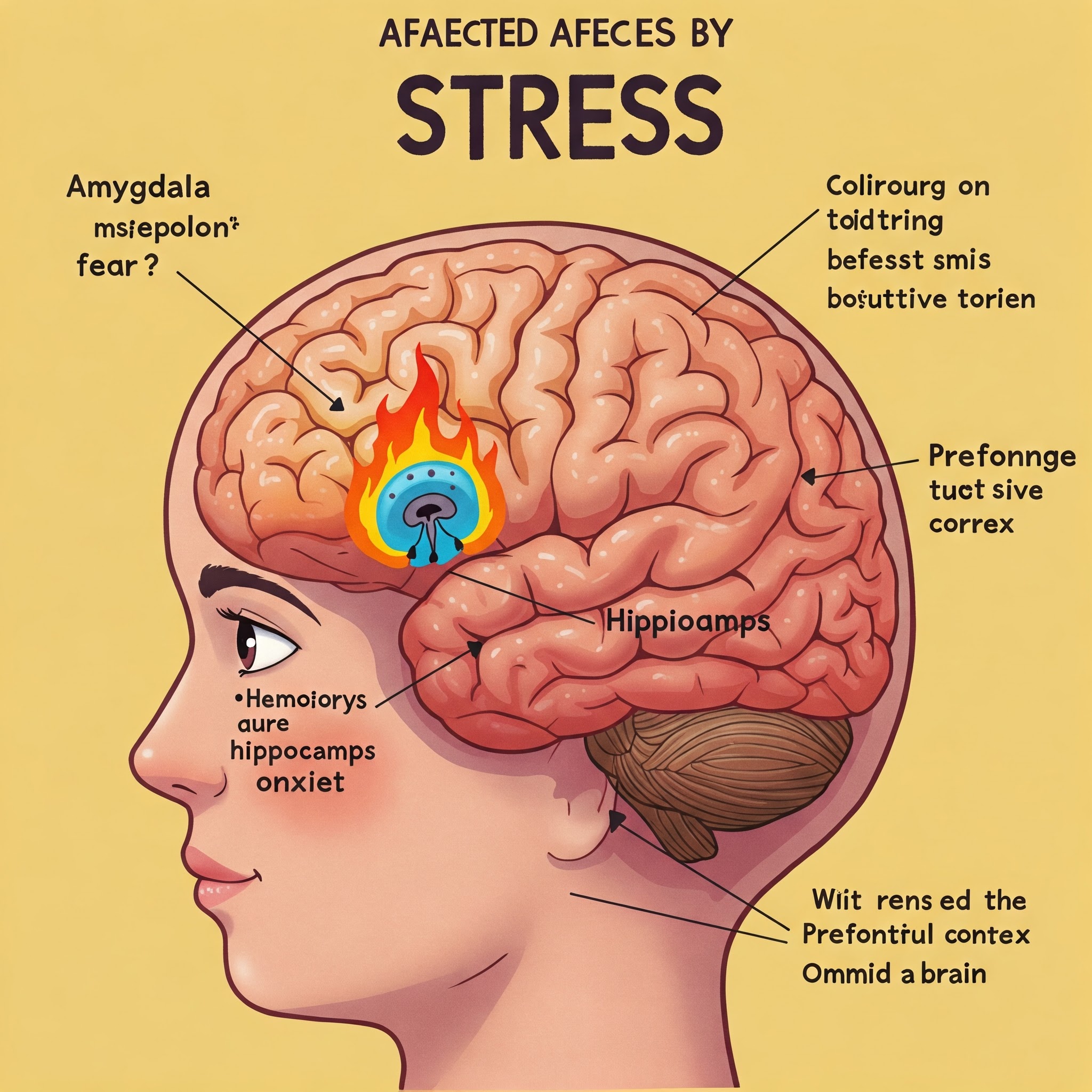

Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, triggering the release of cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. While short bursts of cortisol help the body respond to immediate threats, prolonged exposure—often seen in children experiencing poverty, neglect, abuse, or instability—can impair brain areas such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. These regions are crucial for memory, emotional control, and decision-making.

Impact on Cognitive and Emotional Development

Children exposed to chronic stress often show difficulties with attention, learning, and memory. Studies using MRI scans reveal that their brains may have smaller hippocampal volumes and altered connectivity in regions responsible for executive function. Emotional development is also affected. Stressed children may struggle with emotional regulation, experience heightened anxiety or depression, and exhibit behavioral issues.

These changes are not only neurological but also behavioral. For example, children raised in high-stress environments may develop hyper-vigilance or distrust, which, while adaptive in threatening situations, can hinder social interactions and academic success.

Socioeconomic and Environmental Contributors

Stress in childhood often correlates with socioeconomic factors. Children living in poverty are more likely to face food insecurity, unstable housing, and limited access to healthcare and education. These environmental stressors compound over time, making them particularly damaging during developmental years.

Moreover, parental stress can trickle down to children. Caregivers experiencing financial hardship, mental health issues, or a lack of social support may struggle to provide the stability and emotional security children need.

Role of Protective Factors

While the effects of childhood stress are concerning, they are not irreversible. Protective factors—such as supportive relationships with caregivers, access to mental health care, and enriching educational experiences—can buffer the effects of early stress.

Positive environments can help restore healthy brain development by promoting resilience and neuroplasticity. Programs focused on trauma-informed care, early childhood education, and community support are showing promise in helping at-risk children thrive despite early adversity.

Policy and Public Health Implications

Recognizing the long-term impact of childhood stress is prompting policymakers to invest in early intervention. Governments and organizations worldwide are expanding access to mental health resources, parenting programs, and early education initiatives.

For instance, in the U.S., the CDC and local health departments are rolling out campaigns to raise awareness about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their effects. Similar efforts are underway globally to integrate mental health screening into pediatric care and improve social services.

Conclusion

The link between childhood stress and brain development is undeniable and significant. As we gain deeper insights into how early experiences shape lifelong outcomes, the need for proactive, compassionate, and science-based responses becomes ever clearer. By addressing the roots of childhood stress and supporting families and communities, we can help future generations reach their full potential, both cognitively and emotionally.